While there are films that can be summarized in one line, “The Color of Pomegranates” by Sergei Parajanov is a film that resists this urge completely. To say that it is a biographical film of the 18th-century Armenian troubadour Sayat-Nova is to both state the truth and be inaccurate at the same time, since, after all, the poet’s biography is the whole point of the film. Parajanov also overthrows the whole concept of storytelling in favor of presenting us with a series of images that seem far more akin to illuminated manuscripts or icons than they do to anything remotely approaching storytelling.

The movie is one of the examples of how Parajanov works and tells us that it is “not something to be watched in passing,” but to be viewed with some patience and respect. Parajanov breaks down Sayat-Nova’s life into eight episodes and presents us with the childhood, youth, poet, court, love, monastic seclusion, decline, and death of Sayat-Nova. Each episode is done as a ritual, with actions, objects, and colors expressing meaning as words and dialogue would.

From Childhood to Eternity: Sayat-Nova’s Life Rendered in Symbolic Imagery

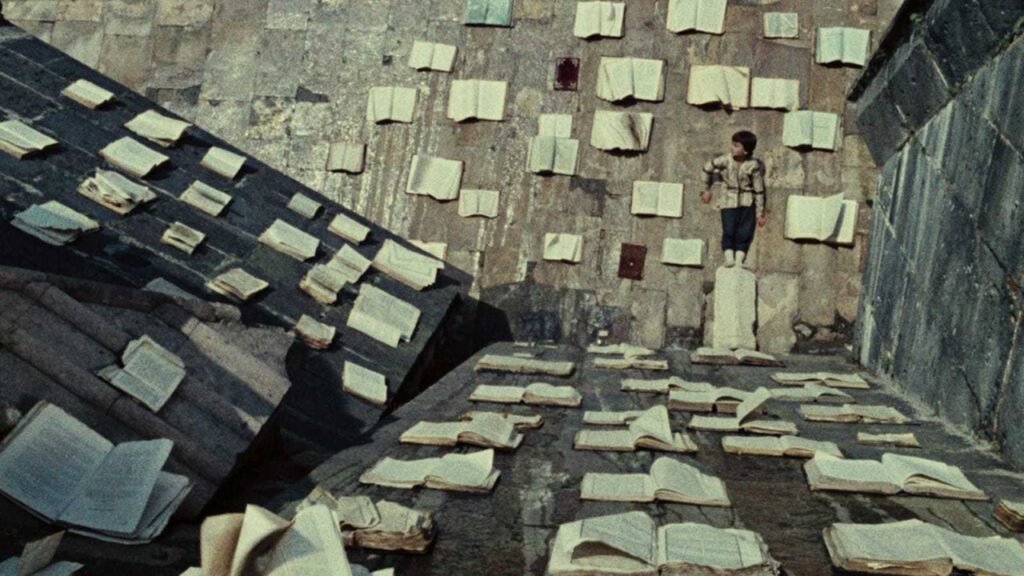

The first images introduce the theme of wool hung out to dry, pomegranates opened and bleeding, and manuscripts submerged in water. The young Sayat-Nova is surrounded not by toys and playmates but with the things that will recur throughout his life. The artist offers us a glimpse into textiles, books, and ceremonies. For Parajanov, the poet’s childhood is not a preservation of innocence but an initiation into the symbolic world of Armenia.

And, as the young Sayat matures, his desire also makes its entry, but in an encoded form. We witness the entry of a woman through a veil, with ripened fruits bursting open, and fabrics unfurling themselves in multi-colored spread. The poet, represented through Sofiko Chiaureli, appears in an androgynous form, reminding that the process of creation itself lies beyond gender. In his youth, Sayat-Nova finds his outlet at the Georgian royal court, which is portrayed by Parajanov as Breathtaking and stiff, as if the courtiers are positioned like chessmen, with the royalties covered in superior fabrics, and the movements locked in ritualistic repetition. In this royal court, the splendor of creativity prospers, yet somehow only under the observation of power.

The world of Sayat’s love, which may be with Princess Anna, takes place in several depictions of symbols. We witness the lovely peacock prancing its way, grapes and pomegranates bursting, and veils being hidden and then revealed. Nothing is spoken, but the sense of longing is conveyed through every action, as if showing us that their love will have to remain unrequited and relegated to the realm of a memory, rather than an experience. Disillusioned with the notion of love and heartbreak, Sayat-Nova seeks solace within the walls of the monastery, and soon enough, the colors become somber, as we see monks wearing black robes, animals being led for sacrifice, and rituals being performed with mournful exactness. This is more than a rejection of love; this is the rejection of the world itself, since it represented a turning towards the eternal.

Sergei Parajanov’s Symbolic Cinema Uses Objects as Storytellers and Vessels of Cultural Memory

In the concluding movement, the poet grows old and dissolves away. His clothes are packed away, and his body is wrapped up, as the pomegranate starts bleeding again. The imagery comes full circle, thus ending the life cycle. Death is shown, not as an end but as a transition.

One of the most interesting features of Parajanov’s technique is the manner in which he allows objects to be used as characters. The framing and depiction of wool, manuscripts, fabric, fruit, musical instruments, and livestock all function as silent narrative tellers. In fact, for Armenians living under Soviet censorship, such images held extreme significance because they were imbued with the meanings of memory, belief, and nationality that could not be articulated aloud. The pomegranate, so iconic in the imagery of the film, is itself a symbol for Armenia, as it represents the fertile, the wounded, and the resilient. With every re-emergence of the pomegranate, there is always a reminder of sacrifice and survival. The late 1960s was a period when Soviet cinema was yet to break free from the constraints of Socialist Realism, which stressed the need for clarity, heroism, and meaning. In a period when the need for outspoken, daring films was necessary to make a statement, Parajanov did the exact opposite, making a film that boasted no dialogue-driven plotlines, no heroes of socialism, and certainly no compromises. It is little wonder, then, that the state stepped in to re-edit and censor a substantial amount of footage.