Dating back to the 5th century BC, The Oresteia, written by Aeschylus, has always been regarded as a groundbreaking text of Western drama. Consisting of Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides, The Oresteia represents the sole surviving ancient Greek drama trilogy. Beyond being a set of tragic plays, the Oresteia trilogy that was released back in the year 1982 follows a process of moral and political development—the transition from revenge to common law and from punishment meted out by gods to punishment prescribed by humans.

Performed for the very first time in 458 BC, the trilogy was awarded the top honor at the festival of Dionysia and has survived for nearly two and a half thousand years because of its simplicity and subtlety. While its purview lies with the cursed House of Atreus, its relevance does not.

Bloodshed, power, and moral ambiguity

The Agamemnon, the first play in the trilogy, opens with a triumph but concludes with a murder. Agamemnon comes home victorious in the Trojan War but gets murdered by his wife, Clytemnestra, for sacrificing their daughter, Iphigenia, in the Trojan War. Clytemnestra’s act of murder has both a rationale behind it and its justification pronounced aloud. Aeschylus fails to depict her merely as the villain. She is indeed a murderer, a mother, and a queen, claiming her place in a world of male-dominated violence.

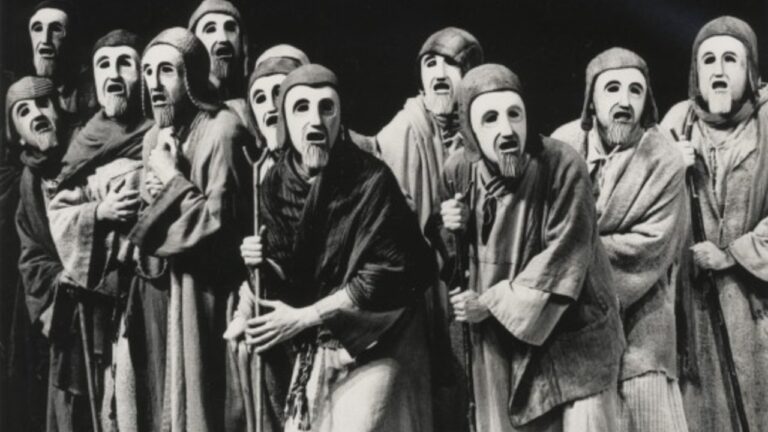

The moral conflict escalates with The Libation Bearers. Orestes, urged by Apollo, kills his mother to avenge his father. The matricide, far from an accomplishment, becomes an inevitability followed by terror. The Chorus participates and urges vengeance rather than just observing; it illustrates how violence begets itself by virtue of group admiration.

Throughout these first two plays, justice is synonymous with bloodshed. Every revenge act is at the same time understandable and unjustifiable. There’s no easy moral message in Aeschylus. There’s only escalation.

Condoned Crimes: From vengeance to present-day justice

This decision is brought in The Eumenides. Orestes is chased by the Furies for murdering his mother. He turns to Athens for refuge. The goddess Athena makes her appearance, and instead of an eyeful of blood and murder, there is an eyeful of justice in the court of Areopagus.

The verdict in this trial has been carefully weighed. A tie case must have the casting vote, which Athena gives, and this leads to the acquittal of Orestes. What is important, however, is that she changes the Erinyes from avengers to guardians of order. Revenge is thus not undone but rather channeled into law.

The ending of the play represents its adherence to the changing dynamics of Greek thought, from the idea of blood guilt to the concept of justice through instituted systems. While it is difficult to gauge the views of Aeschylus regarding the reforms of Athens, it is apparent that the trilogy is well-informed about politics.

The Oresteia is relevant because it portrays violence, not spectacularly, and justice, not definitively. It asserts that order is not a natural phenomenon but an edifice that needs constant maintenance, and that the survival of civilizations is accomplished not by removing conflict but by learning how to accommodate it.