The movie Werckmeister Harmonies, directed by Béla Tarr, is the paradigmatic example of the indifference of the universe and the breakdown of society, being a movie that elevates the frozen roads of a Hungarian provincial town to the level of a parable on the exhaustion of civilization. Shot in severe black and white, with thirty-nine successive shots, Werckmeister Harmonies is much more an observation of the metaphysical order than a story, an act that is carried out with the inevitability of a dead star. This is what Tarr, as director, demands, and also co-writer László Krasznahorkai, who try to reconstruct the ruins of a society that no longer believes in reason or transcendence, in a world in which any attempt to impose an order on it is destined to produce only chaos.

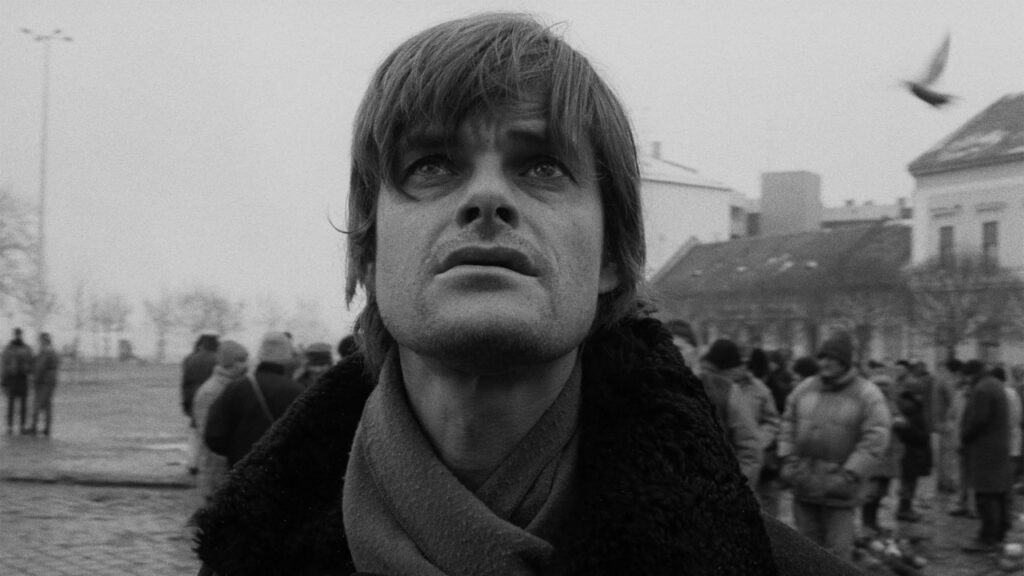

This film is about a young man named János Valuska, who is a thoroughly kind-hearted individual, and he just wanders around doing some odd jobs for the people in the town and trying to find a way to connect with people in a world that has forgotten how to feel.

Béla Tarr’s Winter Town Faces the Rise of Fear, Hysteria, and Ethical Paralysis

The tone that is created in the introduction continues throughout the movie. In a darkened tavern, János is instructing a group of drunken men in the way of simulating the movement of the Sun, the Earth, and the Moon. For a brief moment, János was able to inspire an illusion of harmony. The concept of bodies revolving around each other in a state of perpetual equilibrium begins to instill an idea of harmony that would be systematically debunked in the following film. Emerging from the tavern, the streets are deserted and lifeless, and the brief warmth of illusion is quickly extinguished.

The guardian of János, György Eszter, a reserved music theorist, is disturbed by the idea of harmonic systems. He thinks that the tempering scale of the eighteenth century, perfected by Andreas Werckmeister, has caused the corruption of the purity of sound to make it rational. The imperfection, according to him, represents human civilization itself and the way in which the world has been tuned to favor humanity, leading to the loss of truth in the process. However, with the escalation of the unrest, the strength of the Prince is enough to turn idle chatter into chaos. The people, driven by a sense of injustice and collective delusion, march through the night. Tarr captures their movement in a single, continuous tracking shot, stripping away all dialogue and music. They pour into a hospital, destroying everything in their path, until they finally come to an old, weak man. Confronted with the absolute truth of human weakness, the mob stands still. Violence gives way to silence. It is a moment of moral understanding, and it occurs in an instant. The town is in a state of paralysis. János, who has lost all hope for the future based on what he has seen, is taken away to an asylum. György, who had once been so passionately dedicated to his project of repairing the disharmonies of the world, now recognizes the pointlessness of his enterprise. The whale lies abandoned in the square, its secret out, its massive carcass rotting in the cold.

Werckmeister Harmonies Utilizes Circular Time, Stasis, and Patience to Examine the Inevitability of Decay and Emptiness

In the final tableau, the whale lies motionless in the square, exposed to the elements and the bitter bite of the wind. It is at once monument and corpse, sign and thing. János no longer looks at it in awe; he simply acknowledges it. The secret is out, and nothing is left but its presence. Thus, Tarr ends his film not with revelation but with perception, the action of seeing after all the meaning has been drained away. Werckmeister Harmonies ends in stillness rather than resolution. All systems are down, whether it is the musical or the moral, and what is left is the hum of life, which is at once cloudy and indifferent, humming through an empty world. Of course, one thing is clear: that the lack of emotional resolution or salvation in the film means that it is very frightening indeed. Nothing changes or is unleashed in Tarr’s film; only exhaustion is left. But the commitment to this exhaustion is what distinguishes Werckmeister Harmonies from other films. In each scene, the audience is tested with endurance as it stretches the action to a point where its redundancy is no longer relevant. It is this stretching out of time that enables Tarr to make the implication that life goes on despite the loss of purpose. Of course, this is not pessimistic nor sloppy filmmaking, as it is ultimately a statement of observation that does not have any pretension to it. In fact, this is a world wherein beauty resides in the image, and meaninglessness resides in the content without conflict.