‘Frida: Naturaleza Viva,’ which is globally known as ‘Frida Still Life‘ (1983), made by ‘Frida: Naturaleza Viva,’ or as it is internationally recognized, ‘Frida Still Life‘ (1983), by Paul Leduc, would certainly not fall in the category of a typical biographical film, or at least not in regards to a Frida Kahlo audience seeking a definitive presentation of the life of this great artist. None could hope to find that here. But what we do know is that Paul Leduc has provided something that is much rarer, something which would only have been approached by no one. As far as Frida Kahlo herself is concerned, he certainly gave it his best to capture the same essence of beauty in terms of pain and honesty that she has depicted.

The movie begins at the end, as we see Kahlo, played by Ofelia Medina, lying on her deathbed with all the objects and memories floating in the air like restless spirits. Then her life begins in bits and pieces—childhood marked by polio, the accident on the bus that broke her spine, her passionate and tumultuous life with Diego Rivera, her illness, and her indomitable spirit that survived every surgery and every betrayal. Leduc does not relate these events in a straightforward manner. They come to us as memories do, which is not linear but flowing, one picture fading into another.

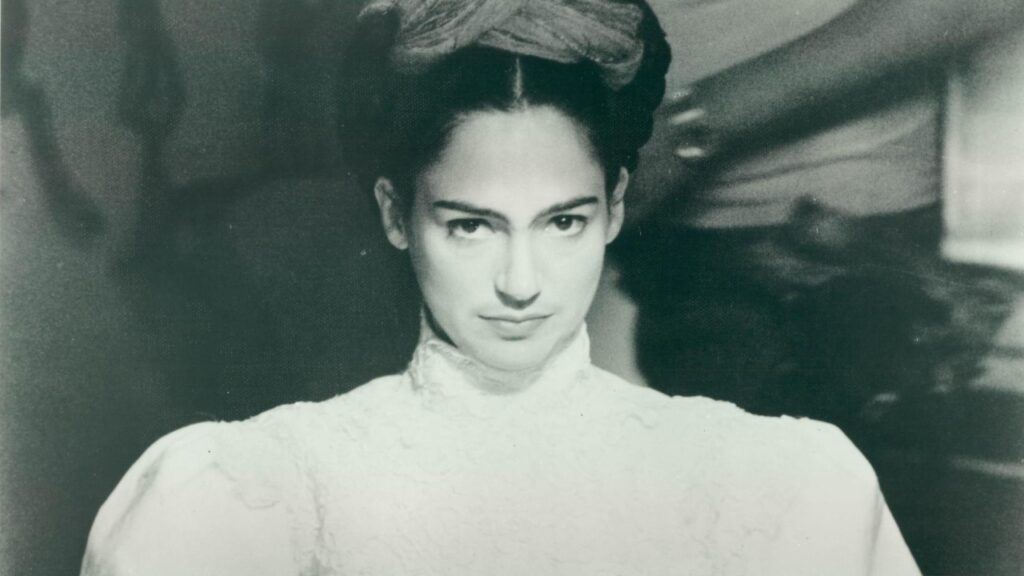

Ofelia Medina and Paul Leduc Transform Frida’s Pain, Passion, and Resilience Into a Masterpiece

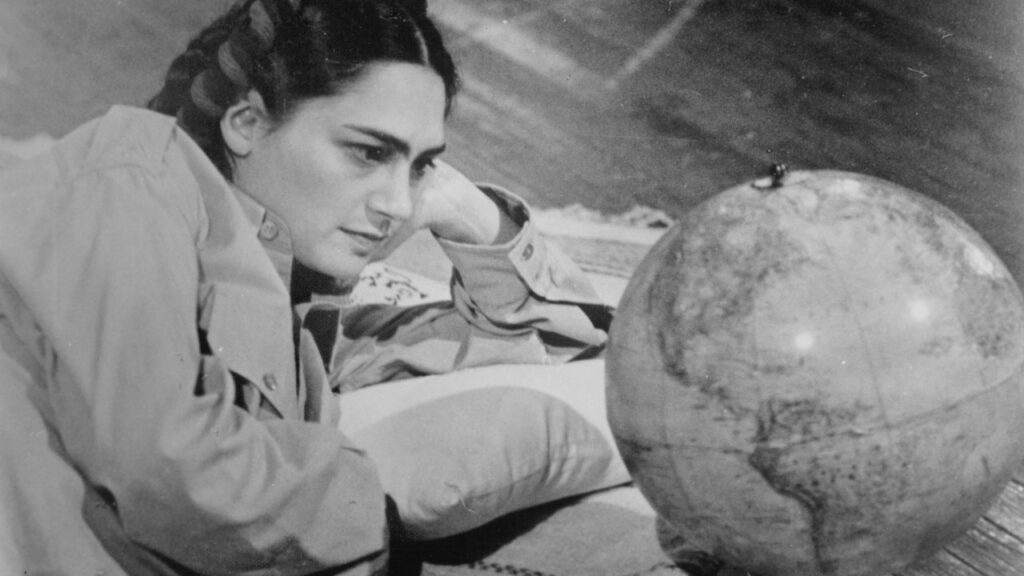

This narrative form is not just for show. It reflects exactly how Kahlo herself dealt with time in her artwork. In her self-portraits, past and present intersect: there is a broken column situated in her spine, blood spots on her dress, vegetation growing around her body. Leduc carries this sensibility over into his film. A spat between household members cuts suddenly to dreamlike sequences of the hospital. Dialogue is sparse and often truncated. Dialogue gives way to music, silence, or the gaze of Medina’s eyes. There is something chillingly beautiful about it. It is not that the viewer “learns” about Kahlo; rather, we are in her world, where pain and pleasure coexist within the same frame.

Ultimately, the key to this success is the performance of Ofelia Medina, and while she does not rely on caricature or hyperbole, she conveys Kahlo’s wit, her sexuality, and the defiance with which she faced both the fragility of her body and the infidelities of her husband. Medina has said that she worked extensively to absorb the life of Kahlo, and it shows. Frida is neither a martyr nor a victim but a strongly alive woman who smokes, laughs, suffers, and always comes back to the canvas as a means of survival. The film is carried by a strong physical performance from Medina, who conveys Kahlo’s strength even when she’s bedridden.

The visual aesthetic of Leduc fights the urge to replicate Kahlo’s artwork in a literal manner, as was seen in later films. Instead, he establishes a visual aesthetic that is an extension of her artwork. The long and static shots are almost like tableaux, with bursts of color from her palette, the shadow and light defining her body as both subject and canvas. An indirect approach is more valid than any direct one. Instead of reducing Kahlo to an object of spectacle, it lets her inner world define the space of cinema.

However, rather than just concentrating on the film’s visual aspects, he ensured that music is given its due importance as well. This includes traditional Mexican songs, revolutionary songs, as well as moments of silence, which punctuate the story because they place Kahlo in her context while also adding to the emotional impact of the story. The music immerses rather than underscores or explains. This can turn a hospital room into a place of ritual or a family gathering into a memory fraught with sadness just because of a melody.

Art, Humanity, and the Woman Within

The Kahlo and Rivera relationship, so often sensationalized in popular histories, is handled here with subtlety. Their love, their betrayals, and their reconciliations are not theatrical confrontations but patterns, an endless cycle of need and desire. The muralist is ever-present, but it is Kahlo’s world that defines the film. It is a subtle shift from the larger-than-life muralist to the woman who was, in her own life, relegated to secondary status but has since become iconic.

What makes Frida: Naturaleza Viva so durable is its determination not to mythologize Kahlo. The film does not turn her into a symbol of suffering or a banner to wave behind political agendas. It chooses to show her as a human being, who has converted her pain into her art without ever losing her sense of humor or her appetite for life. By the time it returns to her deathbed, the viewer feels as if they have experienced a consciousness rather than a biography. Typically Mexican in its intimacy, the 1983 film long predates Kahlo’s international sanctification. It is the work of a Mexican director and cast, unencumbered by the task of transposing Kahlo into a commodity suitable for export abroad. Its focus is local, cultural, and significantly, personal. And it is precisely this that lends the film its immediacy, its raw edge, which subsequent appropriations lack despite their sophistication. Frida: Naturaleza Viva is no easy watch, as one must remember that its very non-linear narrative, minimal dialogue, and slow-burning rhythm require a certain tolerance. However, for those willing to immerse themselves in its beauty, they must prepare to receive something much more enriching than mere knowledge, since this is an experience of the fabric of life itself, lived with passion and pain, and rendered with loving care. Within its fractured narrative, one sees the completeness of a woman who chose to portray her own reality through her paintings.