‘Andrei Rublev’, made by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1966, is a historical film based on the life of the Russian icon painter of the 15th century, Andrei Rublev. The film takes place in medieval Russia, which is experiencing the reign of war and spiritual turmoil. Instead of biographical data, the film is concerned with how an artist copes with the presence of violence and doubt in his society. This is done through the episodes in which Rublev maintains and then loses and again regains his faith in humanity and in his art.

The movie starts with a prologue in which a man tries to fly using a homemade balloon. The villagers chase him as he flies for a few seconds before falling. Although this scene is not connected to the rest of the movie, it introduces the theme of human aspiration and failure. This scene introduces the theme that every creative act is an act of risk and misunderstanding.

History, Suffering, and the Artist’s Conscience

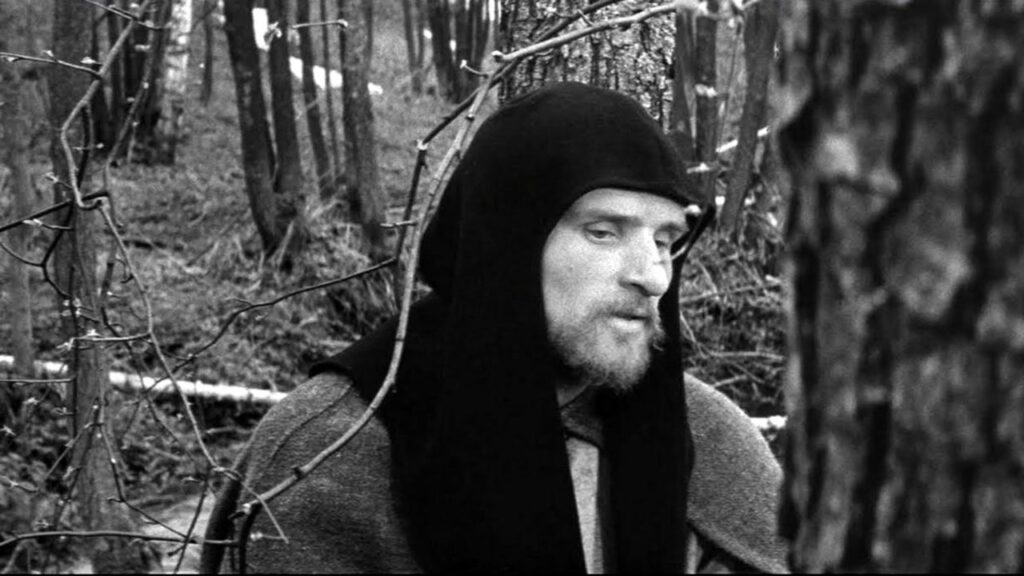

The story shifts to Rublev and his fellow monks, Kirill and Daniil, as they journey through the countryside in search of employment. During this journey, they come across a jester entertaining peasants with derisive songs about the nobility and the clergy. The soldiers take the jester away, and the monks remain silent. This scene sets the context of the movie; words and art can trigger retribution, and the character Rublev’s natural response is to be passive.

Later, Rublev encounters Theophanes the Greek, a more experienced painter who invites him to help paint a cathedral. Through their conversations, the contrast between the two men is revealed. Theophanes is a pessimistic man who views humanity as flawed, while Rublev is a compassionate man who thinks that spiritual truth can be expressed through art. This dialogue reveals Rublev’s earlier conviction of the divine function of painting, but also its vulnerability in a brutal world.

The following significant event portrays Rublev seeking shelter in a storm and observing a Passion play performed by villagers. However, the spectacle, intended to demonstrate their devotion, is disrupted by soldiers dispersing the crowd. This reflects how religion and violence coexist within the same arena. Rublev’s conviction about the importance of art will now begin to falter.

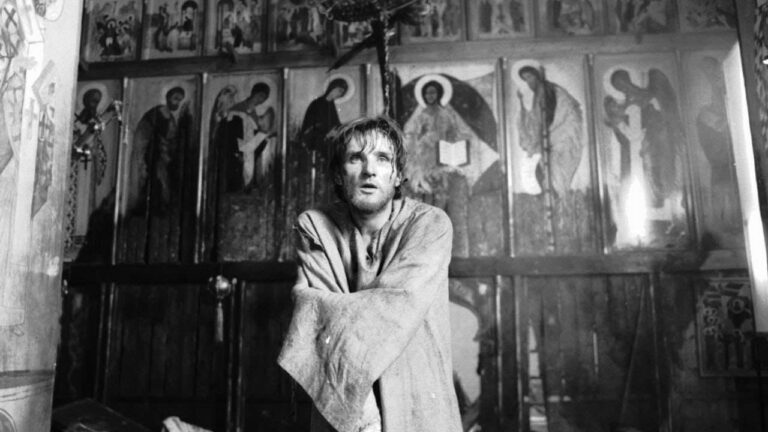

The assault on the city of Vladimir marks the turning point in the movie. The Tatar army, assisted by Russian traitors, sets fire to and destroys the city. Churches are plundered, and the inhabitants are slaughtered. Tarkovsky records this raid with long takes that reveal the breakdown of order and faith. In the midst of this mayhem, Rublev kills a man while attempting to safeguard a woman, thus violating his monastic oath. This sin leads him to become mute and depressed. He renounces painting completely, as he is convinced that his work cannot coexist with the violence that surrounds him.

The Struggle and Resurrection of Andrei Rublev

When he is assigned to do a fresco of the Last Judgment, Rublev refuses. He finds it hard to show eternal torment when he has witnessed enough pain in life. His silence is both protest and punishment. The scene then shifts several years ahead to a time of partial recovery in Russia. There is a young boy named Boriska, who knows the secret of making church bells, which has died along with his father. He is assigned a project and heads it under extreme pressure. Rublev, still speechless, observes the struggle of the boy. But when the bell rings successfully for the first time, Boriska bursts into tears and confesses that he never knew the secret in the first place. Rublev tries to comfort him and only then speaks, telling the boy that he will resume painting, while the boy has to continue making bells. It is in this conversation that Rublev regains his faith in humanity. Indeed, in the epilogue, the black and white photographs change to color as Tarkovsky presents the actual icons that Rublev is said to have created. After witnessing such destruction, the fact that the paintings exist at all is a testament to survival rather than victory. This final message of the film is that artistic expression endures through pain and that belief in the creative process can, indeed, survive political and personal failures. The deliberate pacing, attention to nature, and unwillingness to simplify feeling in Tarkovsky’s Rublev is a case study in the relationship between art, silence, and beliefs under pressure, and it remains one of the most intense studies of the role of the artist throughout history and the ways in which beauty persists.