Fifty years before the advent of Cahiers du Cinéma’s Politique des auteurs, Dziga Vertov’s film continues to be the most radical work in cinema history. Vertov’s film is a silent documentation that does away with storytelling, actors, and intertitles in favor of its own observation of the act of cinematography. The footage was shot by Vertov’s brother, Mikhail Kaufman, while the film was edited by Yelizaveta Svilova. It observes daily activities in Moscow, Kyiv, and Odessa in the space of one day.

When the film initially came out, it received nothing but negative reactions. Critics thought that Vertov concentrated more on technique and less on meaning, and also that his rhythms were completely strange and alienating. Years later, Man with a Movie Camera came out as one of the most influential films in modern cinema and has been ranked one of the greatest films of all time in various Sight & Sound Polls.

A city observed: a medium exposed

“Man With a Movie Camera” depicts city life from dawn till dusk with neither character nor plot. Employees punch in their time, machines roar to life, couples marry and divorce, children are born, and crowds accumulate to engage in sport and entertainment. Instead of weaving these elements into a plot, Vertov arranges them in terms of rhythm and movement. Editing is the dominant language in the movie.

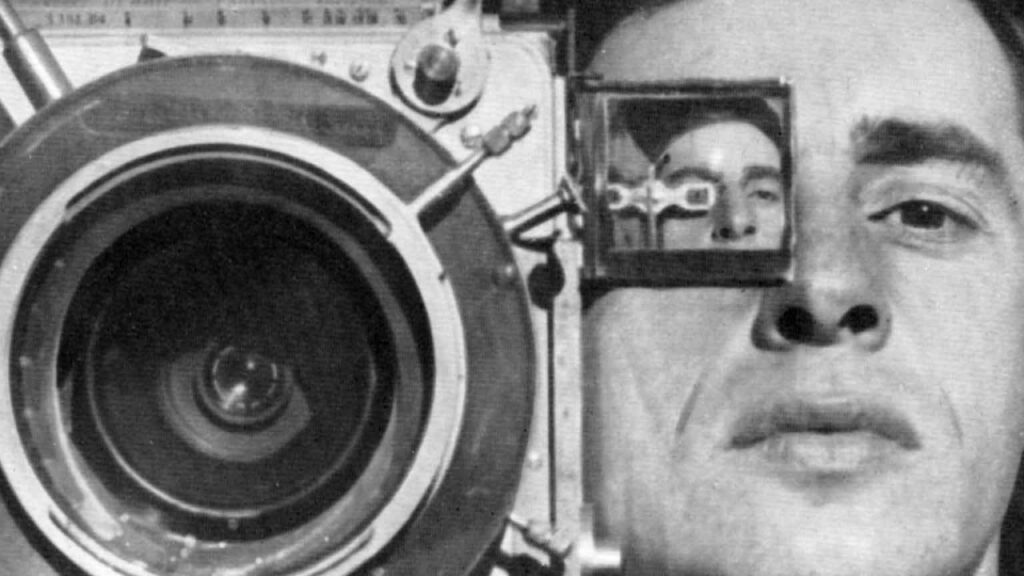

The techniques Vertov uses are still breathtaking today: double exposure, slow motion, fast motion, freeze frames, split screens, extreme close-ups, and montages done at a dizzying pace. The cameraman himself enters the picture, sometimes shooting from impossible angles, sometimes using clever tricks of illusion to change his appearance. The editor is shown working, cutting, and splicing the film that the viewer is watching. The cinema is not a mystery, a trick behind closed doors—it is instead a process made manifest.

Ideology, experiment, and lasting influence

Vertov was a member of the Kinok group, which proposed that fiction should simply be abolished in cinema. Vertov thought that a camera was better suited to discern truth than the human eye and referred to this idea as the concept of “kino-eye.” Man with a Movie Camera was Vertov’s most complete statement of his convictions and a direct answer to critics of his earlier works.

Notwithstanding its message of purity, the film contains advertised events and optical illusions—not as subterfuges but as illustrative spectacles of film’s potential. Stop-motion cameras get up and walk about; chess pieces come together spontaneously; images move backwards. These feature a film that not only records but also reframes reality itself. The importance of the film cannot be overstated. It has impacted various forms of filmmaking, such as experimental films, documentaries, music videos, and editing practices. The film was restored in 2015 based on the only available complete print and even now remains widely distributed and studied as an artifact and a living text.