‘The Grave of the Fireflies’ is one of the most emotionally shattering films ever created, and it came into existence in 1988 by Studio Ghibli. It is derived from a semi-autobiographical short narrative by Akiyuki Nosaka and portrays the devastating impact of war on humanity through the tragic tale of two siblings.

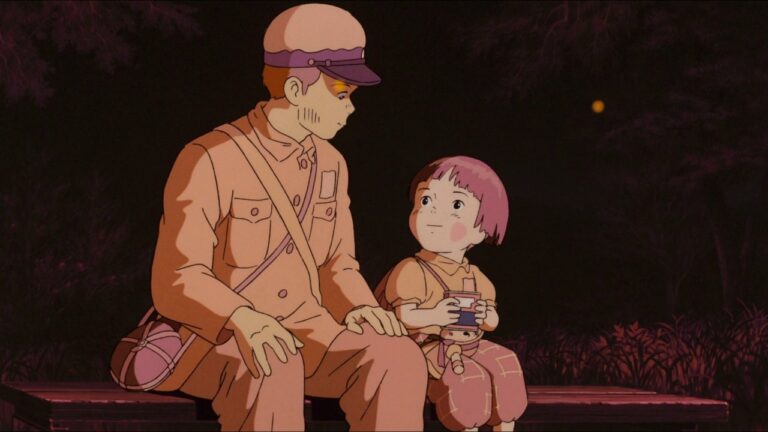

Set in the final months of World War II, the film portrays the struggles faced by 14-year-old Seita and his four-year-old sister, Setsuko, in trying to survive in a Japan that is left in tatters. Right from the beginning, we get a glimpse into how the story will unfold, with Seita’s death on the 21st of September, 1945, in a train station. His spirit, finally reuniting with that of his sister Setsuko’s, gets to live their final few months of life, and we, as audience members, are transported to a world where hope is as scarce as the fireflies lighting up their hut.

A Shelter of Dreams in a World Destroyed

After their mother dies in an American firebombing, Seita and Setsuko have no choice but to survive on their own. They move in with a distant aunt, who initially is generous enough to give them shelter. However, as time passes and the resources dwindle, she also becomes bitter. Her tone of speech becomes sarcastic, her movements no longer contain any warmth, and the children are treated as if they are a nuisance. When they leave her home, it is the start of their subtle act of defiance.

Within the abandoned bomb shelter, Seita and Setsuko have built a makeshift world. They reveal to us the laughter, games, and firefly catching as they try to recapture a semblance of childhood within the wreckage. For a moment, their world is safe. However, we are well aware that this respite is only temporary. Their food supply is running low, Seita is stealing, and Setsuko’s illness is alarming. The moment Setsuko mistakes marbles for candy, believing them to be fruit drops, breaks us. It is not solely her hunger that pains us, but that she still longs to be happy.

The story of Takahata does not manipulate us with sentimentality. The tragedy simply unfolds before us, like a truth that is slowly revealed. Seita returns to the shelter from the city after he hears that Japan has surrendered, and he finds his sister to be delirious and dying when he brings food back to the shelter. Her faint smile as she thanks him for the last time is both an end and a recognition of that fact. Seita cremates his sister’s body and places her ashes inside the candy tin that we had seen earlier at the beginning of the movie.

Seita and Setsuko as Witnesses to Injustice

Fireflies are one of the most powerful symbols used in this film. Fireflies illuminate the nights of the children, beautiful but fleeting, just like bombs that light up the sky with destruction. Setsuko is also depicted as burying the dead fireflies and asking why they had to die so soon, unaware of being prophetic about her own life. This symbolism needs no explanation; it is woven into the story as a reminder that innocence, no matter how small, is not left untouched in the wake of war. To this day, the film still provokes division. It is either a pro- or anti-war statement; others would say it is a pro- or anti-pride and self-reliance film. Again, perhaps that is the point. The Grave of the Fireflies is a story that never really gives an irrevocable answer to anything since, in fact, war never does. In the final scene of the film, the spirits of Seita and Setsuko can be seen overseeing a rebuilt Kobe that is full of life and fireflies. Hunger disappears; loneliness disappears. Whether it is peace or just a reminder of what was needlessly left to die at the hands of humanity is for us to decide.