Warning: This article contains major spoilers for ‘In This Corner of the World.’

There are movies for entertainment, and then there are movies that give us a reason to pause and reflect on the fragile nature of life itself. ‘In This Corner of the World’ is one such movie, and it was produced in the year 2016. It is a Japanese movie, and it is animated by the minds and hands of its creators, such as Sunao Katabuchi and MAPPA, which is based on the life story of Fumiyo Kōno.

The animation within this movie could very easily be the most realistic that has ever been made, but it appears as if each and every image has been firmly planted in reality after research of the landscapes and memories of Hiroshima before the war. Even the extended version of this movie, In This Corner of the World, which came out in 2019, has set the record for the longest animated movie to have ever been shown in theaters.

How Small Moments of Joy Endure in the Shadow of War

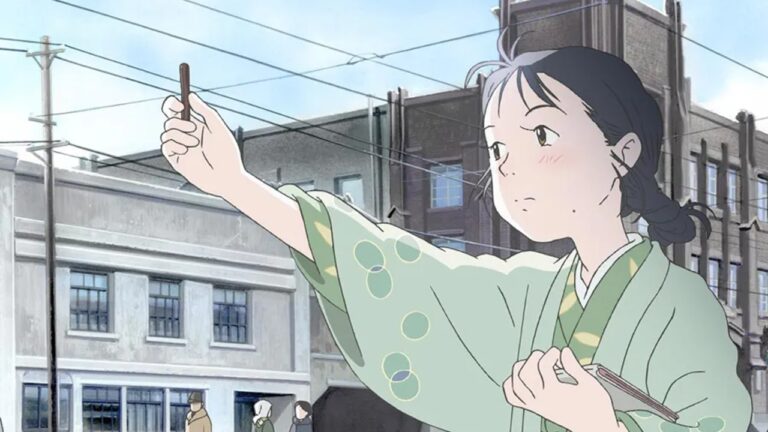

The movie is based on the era of the 1930s and 1940s, and it revolves around Suzu, who is a young girl from Eba, which is a place near Hiroshima. She is a soft, distracted, and artistic girl who loves to draw. It is from her point of view that we get an introduction to the Japan that is soon to be engulfed by the war. Her world is all about the usual activities of life, happiness, and the beauty of nature in her coastal town.

Suzu marries Shusaku, a naval clerk from Kure, in 1943. They live a simple but regular life. But with the increasing intensity of the war, they experience rationing and the sound of air raid sirens. Suzu takes up the task of a housewife, managing the finances and aiding the others in Tonarigumi work. But she never loses her sense of wonder about all this. It is through Suzu that we realize the significance of common people during such times.

The sequences with her niece Harumi are a bit comedic. However, the war draws in around them. Tetsu, who is Suzu’s childhood friend, comes just as he is about to leave for the sea again, and shows his love for Suzu through actions, as the reality of death looms over them. The reality of this encounter that Shusaku accepts is a tribute to the humanity that lies beneath this film. Love in this scenario is not romantic or possessive, but supporting and understanding.

There are silent cells that can go off anytime. When bomb shells fall, at times they do not explode immediately but trigger others because of moments that are small. This tragedy has engulfed Suzu’s life, and therefore she collapsed. She loses her right hand and Harumi in a fraction of a second. The colors fade away, and time slows down. Her tragedy is not dramatized at all. It is silently present in her silence and hesitation, and as we see, she has stopped drawing. The bombing of Hiroshima is revealed not as spectacle, but as distance, a beam of light, a vibration, silence. Suzu and her family watch the massive cloud from afar and later grasp what it symbolized. The presence of terror is also made more intimate in this way. We are left, as Suzu is, trying to make sense of what it means to lose something through newspaper accounts, hearsay, and absence. When Suzu finds out that her hometown is no more than rubble and her family nowhere to be found, the pain is both silent and endless.

The Quiet Rebirth After Unthinkable Loss

But as soon as the war ends, Suzu listens to the voice of the Emperor, who broadcasts the unconditional surrender. The world that Suzu had to conform to and surrender to now turns to Suzu for help. American soldiers come with gifts of food for the hungry population, and a new beginning emerges. Suzu goes to visit her sister Sumi, who has been weakened by radiation sickness. However, the movie never tries to give us a sense of closure since history itself did not give one to those who lived through it. It, however, gives us peeks into grace. Suzu and Shusaku also take in an orphaned girl whom they had rescued after the agonizing struggle that followed the bombing of Hiroshima. The video clip of the orphaned girl is one of the tragedies that has made many viewers cry. She is seen to have led her half-alive mother through the debris of the bombing, and then she dies alone due to her injuries before she was found. Through this act, we do see the lightest glimmer of hope and life. The final acts see Keiko, who is still mourning the loss of Harumi, taking out some of her daughter’s clothes in the hope that they will fit the orphaned girl whom they had adopted. Finally, it ends with Suzu teaching the girl how to sew, her left hand guiding what is left of her right. What remains at the end of the credits, however, is not a sense of closure but reflection. It is a reminder that life itself, besides surviving war, is about finding purpose in a world where hope seems lost. The character of Suzu, who personifies quiet strength and the determination to carry on by creating something, is a metaphor for hope. This movie throws a question, not an answer. What is the meaning of finding hope in the ruins? Perhaps that is the message, and that is what lingers long after the final frame is finished.