When Andrei Tarkovsky embarked on filming ‘The Sacrifice’ in Sweden in 1985, he was living away from his native land and suffering from illness. And he knew he had very little time left. For this reason, ‘The Sacrifice’ has the sense of an ultimate sacrifice—a work of art not for glory but as an act of personal devotion. Indeed, this film was Tarkovsky’s final work, one in which he incorporated all he had ever believed about art, time, and the human spirit.

The plot is about Alexander, a man who lives a quiet life with his family close to the sea, played by Erland Josephson. When his birthday celebrations are in full swing with his friends and family, news of a possible nuclear war spreads through the TV channels. There is no forewarning or reason, just fear and confusion. In the midst of all this chaos, Alexander makes a despairing promise to God. He wishes for the world to survive and that he will give up all that he holds dear if there is peace again in the world. This film is not a story of miracles or calamities but of the price one has to pay for keeping a promise that nobody else comprehends.

When Faith Becomes a Question

Tarkovsky explained The Sacrifice is a parable. It is a story set in contemporary society, communicating in a language of old belief and ritual. We watch ordinary people dealing with something they cannot control, and in them, Tarkovsky asks us what we might do in a situation where we face the end of all things. It is a very slow film, not to mislead us, but to allow us to absorb each glance, each silence, each gesture in which we see what belief is. As a result, it is a very personal experience, as if we were being asked to consider our own sense of belief.

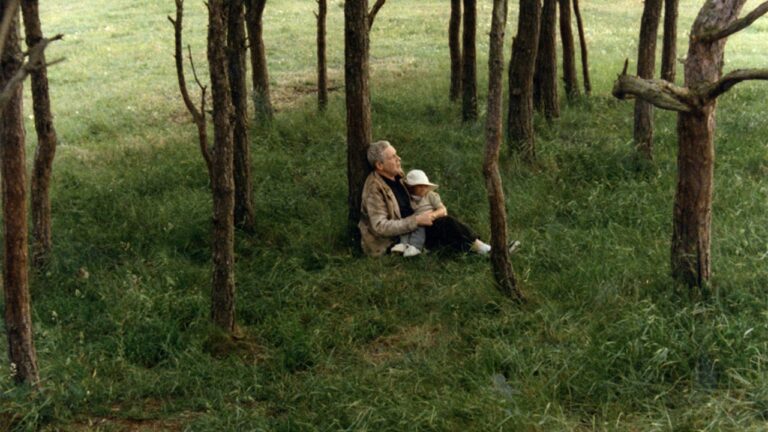

When Tarkovsky moved to Sweden, he chose to work with Sven Nykvist, the cameraman famous for his work with Ingmar Bergman. They created a visual sense that is simple and authentic. The light transitions subtly, and the landscape of Gotland, with the bare fields and gray skies, brings a certain quiet steadiness to the film. Nothing is overt or extreme. The observation of life made through the camera lens brings a sense of the weight of time and the fragility of moments

The Last Gesture of an Artist Through Despair, Hope, and the Choice to Care

The production of the film was challenging. The most difficult scene to film was that of burning down a wooden house. The first attempt was unlucky since the main camera malfunctioned. Most filmmakers would have stopped filming at that point. However, Tarkovsky was not one of them. He wanted the scene repeated. The whole house was rebuilt for the filming. The second attempt was successful. A long sequence of the burning-down house was recorded while the characters watched. This image of destruction is one of the most iconic in cinema worldwide because of its simplicity and the fact that it incorporates elements of loss and rebirth. When “The Sacrifice” was screened at the Cannes Film Festival in 1986, the film won the Grand Prize and the Prize of the Ecumenical Jury. Many film critics considered “The Sacrifice” the culmination of all the themes that Tarkovsky developed all his life long. “In my films,” he wrote, “the struggle between faith and doubt is always the mainspring of the action.” Even then, in films like “Andrei Rublev,” “Solaris,” “Stalker,” and “Nostalghia,” the struggle between reason and the irrational was always there. In “The Sacrifice,” he combined all these into one final act of surrender and demonstrated through the film that even when we are overcome by despair, there is always the possibility of responding through love and humility. The final sequence of the movie comes back to Alexander’s young son as he is watering a parched and leafless tree. Tarkovsky chose this imagery from a story that he regularly told of a monk who every day watered a dead tree until eventually it blossomed many years afterwards.