One of the most important observations in films regarding memory, perception, and time is ‘Sans Soleil’ by Chris Marker. The film was made in 1983, which goes against the conventional narrative of storytelling, as it offers a complex collage of images, sounds, and ideas that include the world.

The film, running for roughly one hundred minutes, is a classic instance of an essay film that has managed to combine elements of documentary footage, travel shots, archival footage, as well as avant-garde. The film commences with a series of letters that have been penned by a cameraman with the name Sandor Krasna to a woman by the name Monique. It is through these letters that Marker has managed to narrate a journey that touches on personal memory as well as cultural memory.

Subjective Memory and the Nonlinear Flow of Time in Marker’s Film

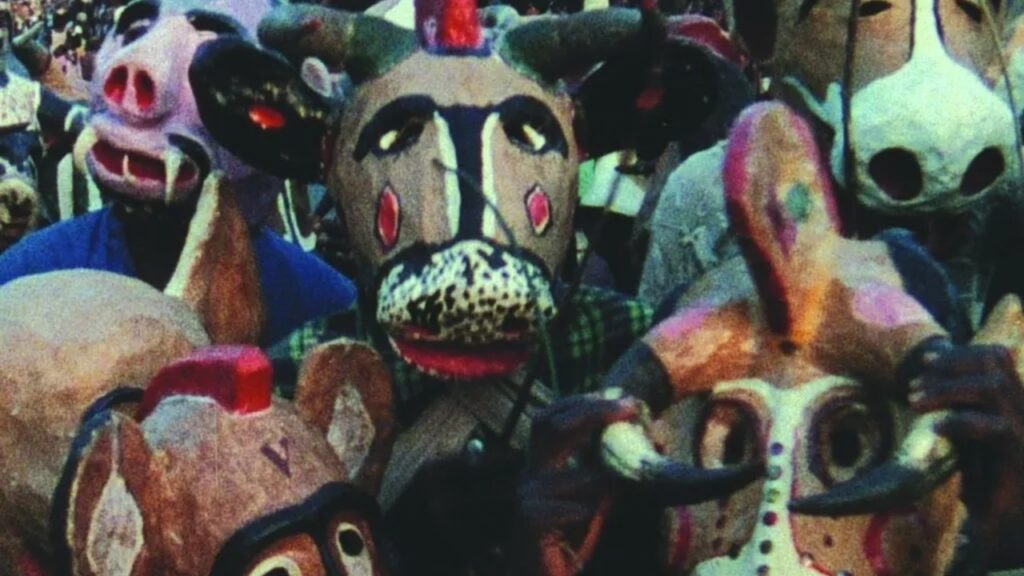

The theme of this documentary is the nature of memory in general. The documentary uses varied images of Japan, Guinea-Bissau, Iceland, and other global locations to understand rituals, life, urban scenes, and artifacts of history. These locations are woven together not with a view to establishing a causal connection between them but for reflection. The comments made in the documentary by Marker always insist that memory is a subjective concern. The images used in the documentary are not objective representations of reality but constitute elements that are assembled through experience. A sequence of images from Japanese everyday life might follow images of soldiers, children, or an archival photograph of war, gesturing towards similarity through the factor of time and space and human experience.

How Sans Soleil Shapes What We Remember

In Sans Soleil, time becomes non-linear, stratified, and fluctuating. In deliberate contradiction to the standard ways of documentary filmmaking and narrative, Marker rejects the linear passage of time. The past and present are conflated in a manner in which historical events resonate through images of the present. A scene from a ritual can be the same as a scene from subjective reflection; a scene from war in an archival image can clarify a scene from the street. The function of the film is to point out that the idea that memory symbolizes experience correctly is not true, but that it translates it into an internal world that is simultaneously present and absent. Marker’s use of the juxtaposition and association of images in cinema proves that time in film can be subjective, a product of human consciousness rather than objective time. The visual aesthetics in Sans Soleil reinforce the philosophical ideas that are presented within the film. In Sans Soleil, the film intercuts between color and black-and-white footage, archival footage, as well as documentary footage, to include staged footage. The Marker camera glides effortlessly through landscapes, skin, and objects to concentrate on details that present a sense of beauty and mortality at the same time. The act of viewing is deliberately invoked, and the viewer is always cognizant of the mediation of sight through the lens of the camera. Each image in Sans Soleil presents the weight of memory, absence, and philosophical contemplation. In Sans Soleil, Marker proposes the notion of responsibility towards the act of recording, as if to record is to create memory. The film also delves into the question of cultural memory, questioning the implications of representation. Footage of Guinea-Bissau intercut with Japanese urban space and Icelandic geography emphasizes the disparities in social structures, scientific achievements, and human experience. However, Marker himself does not present any definitions or conclusions. Rather, he prompts the viewer to think about the question of time, the presence of human creativity, and the integrity of civilizations. The film places the personal memories of individuals within a larger framework of meaning, suggesting that personal memories can no longer be differentiated from collective history. Sans Soleil is one of those rare cinematic projects that succeeds in doing what few films attempt, and it succeeds in using cinema as a platform for philosophical inquiry. Marker, using associative montage, poetic narration, and an unprecedented obsession with the minute particulars of the visual track, builds a stratum based on memory, time, and human perception. Throughout the film, the constant reinforcement of the idea that recording is inextricably linked to interpretation, that memory is constantly being reconstructed, and that human perception molds reality itself takes place. The highly nonlinear cinematic style mirrors the nature of human consciousness itself.